Researchers have developed a way to use smartphone images of a person’s eyelids to assess blood haemoglobin levels. The ability to perform one of the most common clinical lab tests without drawing blood could help reduce the need for in-person clinic visits, make it easier to monitor patients who are in critical condition, and improve care in low- and middle-income countries where access to testing laboratories is limited.

“Our new mobile health approach paves the way for bedside or remote testing of blood haemoglobin levels for detecting anaemia, acute kidney injury and haemorrhages, or for assessing blood disorders such as sickle cell anaemia”, said research team leader Young Kim from Purdue University. “The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly increased awareness of the need for expanded mobile health and telemedicine services.”

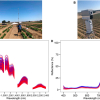

Kim and colleagues from the University of Indianapolis, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in the US and Moi University School of Medicine in Kenya report the new approach in Optica. They used software to transform the built-in camera of a smartphone into a hyperspectral imager that reliably measures haemoglobin levels without the need for any hardware modifications or accessories. A pilot clinical test with volunteers at the Moi University Teaching and Referral Hospital showed that prediction errors for the smartphone technique were within 5–10 % of those measured with clinical laboratory blood.

“This new technology could be very useful for detecting anaemia, which is characterised by low levels of blood haemoglobin”, said Kim. “This is a major public health problem in developing countries, but can also be caused by cancer and cancer treatments.”

The researchers used spectral super-resolution spectroscopy, which uses software to virtually convert photos acquired with low-resolution systems such as a smartphone camera into high-resolution digital spectral signals. The researchers selected the inner eyelid as a sensing site because microvasculature is easily visible there; it is easy to access and has relatively uniform redness. The inner eyelid is also not affected by skin colour, which eliminates the need for any personal calibrations.

To perform a blood haemoglobin measurement with the new technique, the patient pulls down the inner eyelid to expose the small blood vessels underneath. A healthcare professional or trained person then uses the smartphone app developed by the researchers to take pictures of the eyelids. A spectral super-resolution algorithm is applied to extract the detailed spectral information from the camera’s images and then another computational algorithm quantifies the blood haemoglobin content by detecting its unique spectral features.

The mobile app includes several features designed to stabilise smartphone image quality and synchronise the smartphone flash light to obtain consistent images. It also provides eyelid-shaped guidelines on the screen to ensure that users maintain a consistent distance between the smartphone camera and the patient’s eyelid. Although the spectral information is currently extracted using an algorithm on a separate computer, the researchers expect that the algorithm could be incorporated into the mobile app.

“Our work shows that data-driven and data-centric light-based research can provide new ways to minimize hardware complexity and facilitate mobile health,” says Kim. “Combining the built-in sensors available in today’s smartphones with data-centric approaches can quicken the tempo of innovation and research translation in this area.”