Using visible spectroscopy, planetary scientists at Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have discovered that the yellow colour visible on portions of the surface of Europa is actually sodium chloride. The discovery suggests that the salty sub-surface ocean of Europa may chemically resemble Earth’s oceans more than previously thought, challenging decades of supposition about the composition of those waters. The finding was published in Science Advances.

Flybys from NASA’s Voyager and Galileo spacecraft have led scientists to conclude that Europa is covered by a layer of salty liquid water encased in an icy shell. Galileo carried an infrared spectrometer, which found water ice and a substance that appeared to be magnesium sulfate salts. Since the icy shell is geologically young and features abundant evidence of past geologic activity, it was suspected that whatever salts exist on the surface may derive from the ocean below.

“People have traditionally assumed that all of the interesting spectroscopy is in the infrared on planetary surfaces, because that’s where most of the molecules that scientists are looking for have their fundamental features”, said Mike Brown, the Richard and Barbara Rosenberg Professor of Planetary Astronomy at Caltech and coauthor of the Science Advances paper.

“No one has taken visible-wavelength spectra of Europa before that had this sort of spatial and spectral resolution. The Galileo spacecraft didn’t have a visible spectrometer. It just had a near infrared spectrometer, and in the near infrared, chlorides are featureless”, said Caltech graduate student Samantha Trumbo, lead author of the paper.

That all changed when new, higher spectral resolution data from the W.M. Keck Observatory on the dormant volcano Maunakea in Hawaii suggested that the scientists weren’t actually seeing magnesium sulfates on Europa. Most of the sulfate salts considered previously possess distinct absorptions, that should have been visible in the higher-quality Keck data. However, the spectra of regions expected to reflect the internal composition lacked any of the characteristic sulfate absorptions.

“We thought that we might be seeing sodium chlorides, but they are essentially featureless in an infrared spectrum”, Brown said.

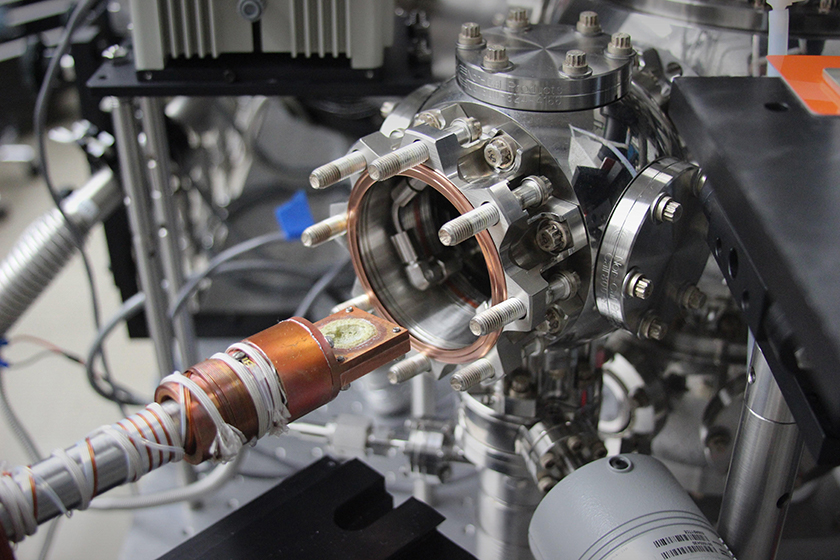

Meanwhile, JPL scientist Kevin Hand had used sample ocean salts, bombarded by radiation in a laboratory under Europa-like conditions, and found that several new and distinct features arose in sodium chloride after irradiation. He discovered that they changed colours to the point that they could be identified with an analysis of the visible spectrum. Sodium chloride, for example, turned a shade of yellow similar to that visible in a geologically young area of Europa known as “Tara Regio”.

In a laboratory simulating conditions on Jupiter’s moon Europa at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, NaCl turned yellow (visible in a small well at the centre of this photograph). The colour is significant because scientists can now deduce that the yellow colour previously observed on portions of the surface of Europa is actually NaCl. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“Sodium chloride is a bit like invisible ink on Europa's surface. Before irradiation you can’t tell it’s there, but after irradiation the colour jumps right out at you”, said Hand.

By taking a close look with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, the research team was able to identify a distinct absorption in the visible spectrum at 450 nm, which matched the irradiated salt precisely, confirming that the yellow colour of Tara Regio reflected the presence of irradiated sodium chloride on the surface.

“We’ve had the capacity to do this analysis with the Hubble Space Telescope for the past 20 years”, Brown said. “It’s just that nobody thought to look.”

While the finding does not guarantee that this sodium chloride is derived from the sub-surface ocean (this could, in fact, simply be evidence of different types of materials stratified in the moon’s icy shell), the studys authors propose that it warrants a re-evaluation of the geochemistry of Europa.

“Magnesium sulfate would simply have leached into the ocean from rocks on the ocean floor, but sodium chloride may indicate the ocean floor is hydrothermally active”, Trumbo said. “That would mean Europa is a more geologically interesting planetary body than previously believed.”