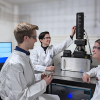

After heart attack, a scar forms on the heart. This scarring leads to poorer heart function and could eventually result in heart failure. Current treatment options are limited and have wide-ranging side effects. A team of researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) have developed new insights into the therapeutic potential of injectable collagen materials for the treatment of heart attack. In collaboration with the team of Emilio Alarcon at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute in Canada (BEaTS team), the MUSC team used matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS), to study how introduced collagen affects and interacts with heart attack scars. The MUSC team was led by Peggi Angel, an associate professor in the College of Medicine.

“Before adopting this technique, our collaborator could only detect the target of the therapy, whereas we can actually detect the therapeutic peptide”, said Angel. “We know where it has spread in the myocardial infarct. It is a better way of detecting and should lead to new therapies, as we will know the exact molecule linked to the site of healing.”

For this study, the BEaTS team prepared collagen hydrogels for delivery to the heart attack area. Hydrogels are large groups of molecules consisting mostly of water. The high water content makes them useful in therapeutics because they can carry treatments and be accepted into the body.

“The biomaterial prepared by the BEaTS team keeps the therapy in a certain location such as the scar”, said Angel. “The cells can sense their presence and that changes how the cells respond.”

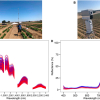

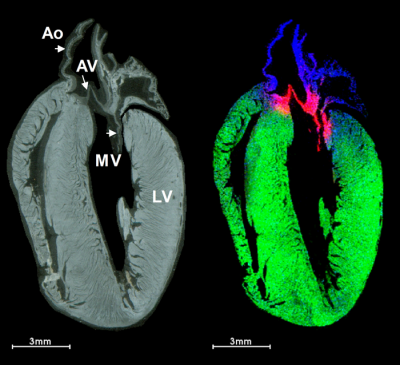

To see precisely where the introduced therapeutic collagen went, the research team used MALDI-IMS to monitor the injected material at the infarct site and to determine how well it spreads to heal the damaged heart. Such information could be very valuable for developing and evaluating therapeutics. In the study, laboratory mice underwent an experimental heart attack and were then treated with human recombinant collagen hydrogels injected into the cardiac muscle. MALDI-IMS was used to distinguish injected human collagen from mouse collagens formed naturally within the body. MALDI-IMS can detect amino acid sequences specific to the human vs mouse collagen.

The work by Angel and team offers a new technique for studying biomaterial injections. Previous studies had only allowed for detection of the result of a treatment, but this study allows for visualisation of the treatment and its spread throughout the heart and wound area. By analysing how treatments and therapeutics are distributed throughout a wound, researchers can evaluate the effectiveness of therapies and, it is hoped, develop new, cleaner techniques to avoid side effects.

Future directions of this research include using IMS to target where therapies are most effective and determine delivery location and timing. Established techniques generally required researchers to know and label what they would be looking for beforehand. Mass spectrometry does not require prior knowledge or information to do experiments and thus allows for novel discoveries.

“Mass spectrometry is easily used as a targeted discovery technique”, said Angel. “We can detect all sorts of molecules, ranging from metabolites to lipids to proteins and even up to DNA.” Equipped with this technology, researchers can gain a better understanding of how collagen dynamics affect heart function, Angel believes. This enhanced understanding could set the stage for the development of therapies that preserve heart function after myocardial infarction.